For decades, we've relied on nutrition labels, comparing numbers and percentages, convinced that they hold the secret to a healthier diet. But have you ever questioned the numbers? Has your health improved?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a strong affinity for labels. They’re now proposing another new rule requiring simple and clear nutrition information on the front of food and drink packages. The main idea is to help people fight the rising tide of chronic diseases.

Although simplification can be beneficial, this approach remains misguided. As you’ll see in this article, nutrition labels have limitations that mask broader issues affecting the food industry. If we’re going to tackle chronic diseases, then labels will never address the cause of the problem.

A Deceptive Trojan Horse

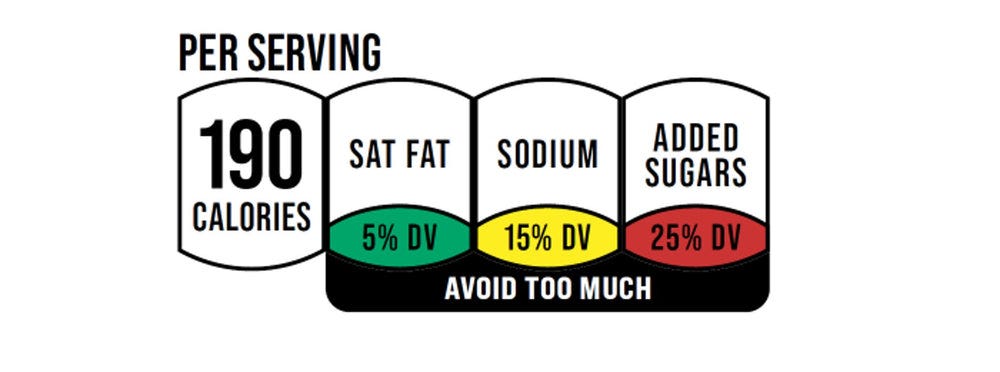

On the surface, these new front-of-package labels appear to be a welcome addition, providing a concise summary of nutrition facts. This is done without replacing the main Nutrition Facts Panel typically found on the back or sometimes side of a package.

Some experts suggest this could prompt food companies to restructure their products to reduce "high" sugar, salt, or fat levels.” Anna Grummon, director of the Stanford Food Policy Lab, told The Times that this is a win for consumers. But is it?

In general, I’m all for more information and more transparency about our foods, but really, how beneficial is it to incentivize retailers selling junk food that’s just above the threshold of adequate nutrition? For example, taking a tiny bit of sugar out of breakfast cereal doesn't make it much healthier. It's like just slightly reducing the sauce on a Big Mac—the product is still mostly unhealthy.

But that’s what the smokescreen is all about. It’s a distraction that gets consumers focused on 3 or 4 isolated numbers while ignoring all that may be bad about the refined food. For example:

Is something low in fat and added sugars OK if it’s higher in refined sodium? What about a low-sodium, no-added-sugar item that scores poorly on the quality of fat content? What if the added sugar column looks good because the food is full of non-nutritive sweeteners? Do you get where I’m going with this? (Step One Foods)

There are levels of nuances that labels miss. Here are some other examples of label deception:

Serving sizes may be deceptively small, making the product seem healthier than it is.

Minor positives, like a small amount of fiber are highlighted while downplaying overall poor nutritional value.

Misleading health claims, such as vague terms like "natural," can create a false sense of healthiness.

Front-of-package labels may discourage scrutiny of the full ingredient list on the back or side.

The last point on this list is what made me so suspicious. Food manufacturers are deceptively evil and know shoppers read little about the products they consume. Having pared down information front and center makes the food appear healthier than it is and disinvites further in-depth scrutiny. Notice the phrase “grab, glance and go” in this very short video.

This emphasis on less product scrutiny isn’t surprising, since food companies and government agencies like the FDA often have close monetary relationships. This connection is akin to the police department closely collaborating with the people they’re tasked with monitoring. In this case, the FDA's new guidelines for labelling food seem to be more about helping companies sell their products than making sure consumers have accurate information.

Whole Food Benefits

Government websites don't often talk about how much better whole foods are compared to processed foods. But despite the fancy new labels, packaged foods with their low calorie, low fat, and low cholesterol content are unable to compete nutritionally with their whole counterparts.

Labels oversimplify the fact that processed foods lack essential components the body needs, while whole foods retain much of their complex nutrient profile intact. So what's most important is not what's printed on the packaging, but whether the food itself is unprocessed.

In other words, the intricate balance of nutrients and phytochemicals found in whole foods is far more valuable than any single nutrient or health claim listed on a label. By focusing on whole, unprocessed foods, we can unlock the full potential of nutrition and give our bodies the ability they need to thrive.

That's precisely why the FDA's new initiative is misguided. It's time to take a more holistic approach to nutrition—and ultimately disease prevention—by eating foods grown locally and in season.

Your presence here is greatly valued, and that’s why all our articles are free on this site. But if you've found the content beneficial, please consider supporting it through a cost-effective paid subscription. This plays a vital role in covering operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent, unbiased research and journalism work. Thanks so much!

If shy about commitments, feel free to leave a one-time (coffee) tip through a Ko-fi contribution! Your generosity is greatly appreciated!

© 2025 (C) Jorg Mardian; "StrongHealth" on Substack.com

Now that just about everything, including most "organic" food, is poisoned, what can one eat to give some time for the body to detox itself? Isn't eating three times a day, for instance, an inheritance from the days, when people needed a lot of calories in order to be able to perform heavy physical labor? As far as I can see, eating little can help.