If you look up "no pain, no gain" online, you'll find a lot of warnings about overdoing it at the gym. There are calls to take it easy, avoid injury, and never push through discomfort. If I didn't know any better, I'd think Google was full of timid experts trying to keep us from getting fit.

According to this thinking, resistance should be barely noticeable, or just enough to remind us we're not sitting on the couch. But we shouldn't push past the point of enduring pain (physical suffering) and stress (mental/emotional suffering) to achieve results.

This kind of advice is making us less resilient as a society. We need to face challenges head-on instead of trying to make everything easy and comfortable. I've personally followed the "no pain, no gain" principle for the past five decades of lifting weights and 25 years of helping thousands of clients as a personal trainer. It proved to be invaluable for instilling determination, pushing through hardships, and overcoming fitness obstacles.

So let’s discuss why proper pain is important during strength training and how to use it to our advantage.

No Pain, No Gain Is Necessary

The idea that you don't need to push yourself to get better or reach your goals is nonsense. If you want to get past the average stage of strength or muscle gains, you have to lift more intensely. Life demands strength, in every nook and cranny. It’s your best friend when you need it and it will never let you down.

In general, we need to do more than we’re doing, not less. Benjamin Franklin illustrated this axiom with the saying: "God helps those who help themselves":

“Industry need not wish, as Poor Richard says, and he that lives upon hope will die fasting. There are no gains, without pains”...In the phrase, Franklin's central thesis was that everyone should exercise 45 minutes each day.

It’s clear that Benjamin Franklin firmly believed in training hard and pushing the body to have excellent returns. That's just common sense and a reality of life. When I train clients, we focus on strength training with intensity. I switch up routines, sets, reps, and types of training often, while keeping a core set of exercises that work well.

Do my clients get sore? Yes they do, and often. Do they see results? Absolutely, much better than most people. Could I get the same results without pushing them out of their comfort zones and making them work hard? Nope, not a chance, and we do this with a very low injury rate.

What I'm getting at is that those who say you don't need to experience some pain or discomfort in the gym probably aren't lifting weights themselves or don’t understand the fundamentals of muscle restructuring.

Progress Versus Harm

There is a vital difference between productive discomfort that leads to growth and progress, and harmful pain that can result from overexertion or improper technique.

If you're new to weight training, you might be surprised by how sore your muscles get after a really tough workout. You might even think you’ve harmed yourself, but chances are good you haven’t. It’s when you overdo training with incorrect form that it can lead to tendonitis, bursitis or stress fractures. So slow down, do things right and and see if pains go away.

No pain, no gain also should not be applied to cardiovascular health, as the heart can get stronger and more efficient at less than maximum fatigue. Moderate effort will not usually cause pain and will still lead to good cardiovascular benefits.

Pain in the chest for those exercising during middle age should be addressed as cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among Americans age 35 and older. Most people aren’t exactly in good shape today.

What Does The Term Really Mean?

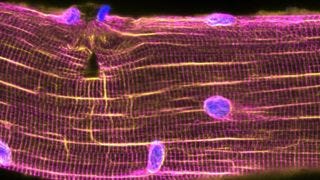

It seems counterintuitive to purposely injure yourself during a workout, but that, in essence, is what you must do to build muscle mass. During intense exercise, particularly resistance training, muscle fibers are subjected to mechanical stress that causes them to tear slightly as a result of the strain placed on them.

But right after you work out, your body starts fixing those tiny muscle tears. The control centers of your muscle cells, called nuclei, move towards the damage and start making new proteins to patch up the torn areas. This repair process is super quick, with most of the fixing done within a day of the initial injury. [1]

One caveat though. The time needed for muscle recovery also depends on an individual's fitness level and the difficulty of the workout. Muscle tearing leads to Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS), characterized by pain and muscle discomfort, a common response to unaccustomed or high-intensity exercise. More challenging workouts might require two to three days for full recovery, while very intense workouts could potentially take even longer [2].

If you work out regularly, your muscles are less likely to tear during your usual exercises. That means they’ve adapted to this particular stage of load. Because they’re now bigger and stronger, they need to be challenged more to keep tearing and growing. [3]

Many experts say this process is unnecessary for muscle growth. One study looked at whether muscle damage and soreness were actually necessary for muscle growth and getting stronger. People new to exercise started with light weights and slowly increased them to avoid pain. Over a few weeks, they got stronger and built muscle without pushing too hard or feeling very sore.

Even though the study seemed to show that you can build muscle without feeling sore, it only looked at beginners. In practical terms, it provided no useful information about how muscle growth works for experienced lifters.

Instead of saying soreness isn't necessary for progress, let's rather see it as helpful feedback for building muscle and strength. In fact, not feeling sore after a workout could mean you're not challenging yourself enough or your body has gotten used to your routine, which means you've stopped making progress.

To negate plateaus, if that is your goal, it’s necessary to exponentially increase the intensity of workouts by either increasing weights, varying reps and sets, adding new exercises, improving technique, or incorporating intensity techniques such as rest/pause and supersets. [4]

Recovery

Lifting heavier weights or training with more intensity is the spark that activates muscle growth. But to avoid injury, it's crucial to use proper exercise technique and ensure adequate recovery between workouts. This allows muscles to adapt to the stress and avoid long-term damage or soreness. [5] If you're still feeling sore after a while, it might mean you haven't fully recovered. [6]

Eating right is key for muscle growth, so make sure to include lean protein in your diet. Also, not getting enough sleep can mess with your form, make you feel less motivated, and even make it harder to lift the same weights you usually do. [7]

In summary, if you’re comfortable with your current training and progress, by all means stick with it. But if you’re looking to take things to a higher level, delayed onset muscle soreness is not a process you should be scared of.

Honestly, it's not that easy to get sore muscles. Newbies get sore easily because their muscles aren't used to working out. But once you've been training for a while, soreness evades you unless you change up your workouts, and push yourself harder. Most people do average workouts and get average results, and that's fine if that works for what they want in life.

Bringing your workout to the next level is hard and requires being comfortable with consistent, hard training, proper technique, and adequate recovery, highlighting the importance of a balanced approach to exercise and recovery for optimal muscle development.

All our resources are available without cost, so please make use of our full, free library. But a lot of work goes into research, so if you found the content interesting and useful, please consider supporting it through a paid subscription. It helps in covering some operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent, unbiased research and journalism work.

Citations:

[Schoenfeld, B. J. (2012). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(3), 808-823].

Rhea, M. R., Alvar, B. A., Burkett, L. N., & Ball, S. D. (2003). A meta-analysis to determine the dose response for strength development. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(3), 456-464. This study found that the optimal recovery time between resistance training sessions can vary considerably between individuals.

[The Repeated Bout Effect - McHugh, M. P. (2003). Recent advances in the understanding of the repeated bout effect: the protective effect against muscle damage from a single bout of eccentric exercise. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 13(2), 88-97].

The Principle of Progressive Overload: National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM). (2018). NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training. (6th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

The Importance of Proper Technique: Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2017). Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- vs. high-load resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(12), 3508-3523.

Overtraining and Injury Risk: Meeusen, R., Duclos, M., Foster, C., Fry, A., Gleeson, M., Nieman, D., ... & Urhausen, A. (2013). Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 45(1), 186-205.

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010): This comprehensive review highlights the importance of rest in optimizing the physiological processes that lead to muscle growth. It also emphasizes that insufficient recovery can hinder progress and increase the risk of injury.

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00971.2016

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128139226000254

https://www.verywellfit.com/strength-training-for-muscle-growth-benefits-workout-tips-6754366

https://www.strongerbyscience.com/research-spotlight-stretching-muscle/

https://cathe.com/muscles-repair-workout-linked-hypertrophy/

It is funny how as an exercise, sports and health "scientist"/coach I have changed my view on this area so often.

Currently, I cannot agree more with you, but for very different reasons. I like that you clearly highlight that "technically" soreness is not necessary for getting any muscle growth or strength improvement - mainly because in the past (and I still believe that this is true for many people in the general public, as they are, like you pointed out, crazy unfit) people thought you need to work out like Arnold or run like Kipchoge to have any benefits.

I agree with you, and I think this needs much highlighting for the general public, because of how bad our general state of health and fitness is. And by "our" I mean world-wide. After decades of working in this area, and seeing/hearing the continuous discoveries and implementations of various training methods and protocols (some of them, being right there at the "cutting-edge" of science myself), it is very clear to me, in an objective way, that nothing that we have done so far is working or having MAJOR impact.

While I am not a fan of calling people "soft" or similar, I actually 100% agree with where you coming from. The physical wellbeing standard, or expectation, that people have for themselves, is definitely "soft" and outrageously low. The amount of time we had people across different training and educational facilities practice their coaching and programming with trainees while claiming that they will deliver them crazy big muscle or endurance gains if they just show up to the gym twice per week for 45 min is quite telling about this (literally, our beginner coaches/students who have 0 previous knowledge assumed that you can go from 30% body fat, 20 kg barbell squat and generally "pear" physique to 10% body fat, 2x body-weight squat and Arnold levels of looks :( ).

Finally, I think a big part of this is of how bad, low and "soft" ;) our general "fitness" and exercise recommendations are.